For over 2000 years magic and witchcraft have captivated the minds of the West, instilling feelings of fear, dread, terror, and, more recently, fascination in the European populous. What started as Greco-Roman and Pagan beliefs became demonized by the Catholic Church into a threat to the natural order and creation itself. While the concept of the stereotypical evil witch figure developed in the Medieval period and flourished throughout the Early Modern, countless modern representations since then have continued to draw from these historic ideals. By analyzing these modern representations, we can not only see how past ideas have continued to shape popular consciousness into the present, but also how contemporary social environments act to shape historical ideas. This paper will be concerned with doing just that; looking at a (semi)modern representation of witches and witchcraft from the first horror novel ever written in the English language to try to unpack the long historical tradition that inspired it. The character of Matilda, from Matthew Lewis’s 1796 book The Monk, can be seen as a composite of both Medieval and Early Modern historical ideas of witches and witchcraft. Drawing on concepts more closely related to that of the Medieval male necromancer than the female witch, Lewis presents us with a powerful image of the social order subverted that can be seen as reflective of the drastic societal upheaval brought on by the events of French Revolution. Lewis’s representation of Matilda, and magic as a whole, can be seen to have been heavily influenced by Medieval beliefs surrounding demonic ritual and Early Modern fears presented in the many demonological treatises produced between the 15th and 18th centuries.

This paper shall begin by considering the identity of the man who wrote The Monk, Matthew Lewis, and the historical context that so greatly influenced his writing. A brief synopsis of the novel, giving consideration to the real-world events taking place at the time of writing, will then be presented, providing the framework from which the analysis of the witch Matilda can take place. Afterwards, we will explore three closely related ideas surrounding Lewis’s representation of Matilda and witchcraft concepts. How and why Matilda should be seen as inspired by historical ideas of the male necromancer and not the female witch, her subversion of the social order as both a temptress and unnatural female, and Lewis’s debt to the writers of Early Modern demonological treatises will all be laid out. Finally, the conclusion will reiterate the key points explored and offer how this study should be understood.

Lewis, born in London in 1775, grew up in a world on fire. Political unrest growing in France, religious riots in the streets of London, working-class movements agitating across the U.K, the old-world order, it seemed, was on the verge of collapse.[1] This then was the backdrop to which Lewis wrote The Monk, a context of a social order, the very foundations of European society, being torn apart and set ablaze. Is it that hard to fathom, then, where Lewis drew his inspiration for the horror and depravity that would characterize his first book? The Monk itself was started by Lewis the same year as the infamous September Massacres that gripped Paris and was completed in 1795, shortly after the subsidence of the revolutionary Terror.[2] While these horrific scenes of violence and anger burning through France and threatening to spill out across the continent would provide a suitable explanation for Lewis’s extreme and brutally graphic horror, they are only part of the picture. The anxieties that gripped England in the face of the revolution in France undoubtedly aided Lewis and provided the ideal atmosphere for him to create a story in which the very social order is being corrupted by dark forces. However, he also had a far more personal history with the events in France that cannot be understated.

In 1791, when Lewis was only a teenager, he witnessed the brutality of the Revolutionaries firsthand. He was in Paris at the time and, while the second-hand fears of the Revolution in England cannot be dismissed, they would have been nothing compared to what Lewis was exposed to in the French capital. Agitators frequently employed graphic images of violence and sexual acts in their depictions of the Church and nobility, an atmosphere that can be seen recreated in Lewis’s choices in representing religious orders in The Monk.[3] This was a time when “prostitution, orgies, sodomy, pederasty, and rape were considered to be the everyday debauches of those in power, and… the guillotine was in fact a comparatively benign fate compared with what the mob might mete out in its parody of justice.”[4] Given this turbulent climate to which Lewis was exposed from such a young age, it is no surprise that the impacts of the fears it generated can be seen reflected in the representations of witches and witchcraft in his writing. Matilda, and the diabolical magics in which she partakes, are shaped as much by the chaos that gripped Western Europe while Lewis was writing as the historic sources he draws from to inform his representation.

While there are several subplots in the Monk, the main story of relevance to our topic is that revolving around Ambrosio, Matilda, and Antonia. The novel is set in Madrid, “a city where superstition reigns with such despotic sway,” home to the Capuchin monastery where many of the events we will discuss transpire.[5] Even the very selection of this scene, Spain, and the choice to represent the monastic institutions as houses of debauchery and sin bears the mark of Lewis’s life. Anti-Catholicism was rife in protestant England, with the 1798 Gordon riots that tore through London being just the latest instance of centuries of religious unrest and intolerance.[6] In its most general sense, the story follows the tale of the esteemed Abbot of the Capuchins. The monk, Ambrosio, has lived his whole life in monastic servitude, being left at the monastery door as a baby. His life of pious religious devotion, however, is about to be turned on its head. Having infiltrated the monastery under the guise of a young male novice called Rosario, the beautiful and mysterious Matilda seduces the monk, convincing him to break his sacred vows of celibacy. It is this breaking of his vows that catapults Ambrosio down a dark and twisted path, descending into the depths of the very worst of human immorality, brutality, and violence. Ambrosio’s insatiable lust causes him to quickly grow tiered on the once captivating Matilda, and so he turns his sights upon the innocent and pure young Antonia, a congregant of his church. Matilda, not upset with the monk’s disinterest, instead offers her help in fulfilling his twisted desire to rob the young girl of her innocence. By invoking demonic powers through ritual magic, summoning Lucifer himself, Matilda enables Ambrosio’s detestable actions that result in the rape of Antonia and the murder of both the girl and her mother. These crimes, perpetrated by the once pious monk and enabled by the sorceress, are all the more grievous when it is revealed that Antonia was actually Ambrosio’s own sister, and her murdered mother his mother too. This once esteemed monk, the epitome of religious devotion, seduced and corrupted by Matilda and the Devil, swiftly comes to embody the very darkest sins of mankind, selling his soul in a truly horrifying and destructive fall from grace. Ambrosio’s fall serves as a stark reminder that even that which is thought to be unbreakable can indeed be broken down to nothing; perhaps another reflection of the anxieties brought forth by the Revolution. Let us now move on to consider the historical inspiration behind Matilda, the figure who catalyzes and drives these awful events

At the opening of this essay, it was asserted that Matilda, our representation of a witch, was more akin to a medieval male necromancer than a Late Medieval/Early Modern female witch. Before this point can be demonstrated, we must first make clear what such a distinction means. You see, for much of the Medieval period, misogynistic gender notions actually made witchcraft, the practice of powerful demonic sorcery, a crime believed to be carried out by men.[7] This was a dominating practice, exerting one’s will over that of the demons you invoked and controlled to do your bidding, and so women were not thought to have the capacity to do so. This view of magic as a form of elite learned necromancy can clearly be seen in the condemnation issued by the University of Paris in 1398. The document discusses magic, but not the maleficia and witchcraft that would come to be associated predominantly with women in the latter part of the Medieval period. This condemnation is concerned with ritualistic demonic magic aimed at summoning and binding demons to the magician’s will.[8] This was deeply powerful magic centred around the idea of controlling and dominating demonic forces, the occupation of educated elite men and clergy members, not women.[9] As is argued by historian Michael Bailey, in the late Medieval period we can observe a shift in magic to a crime associated with females coinciding with a feminization of concepts surrounding demonic sorcery.[10] The shift marks a move away from magic as necromancy and towards magic as witchcraft. This in part revolves around a turn from magic as a form of control over demons and the devil, to magic as a submissive act.[11] The practitioner of witchcraft did not command demons, instead, she submitted herself to them, often sexually, in exchange for the ability to exert supernatural influence on the world.[12] This meant that witchcraft “represented a more feminized form of demonic magic … [and] could be seen as more suited to women than to men, because the power of witches rested on their submission to the devil and their susceptibility to his seductions,” a susceptibility that’s origins can be traced back to the biblical tale of Adam and Eve.[13]

Now the distinction between the witch and the necromancer has been made, it is time to justify why Lewis’s inspiration behind the character of Matilda should be understood as stemming from the latter. To do so, it is best to turn to two specific excerpts from The Monk which clearly show that Matilda’s behaviours are far removed from any form of submissive feminized magic. For, recounting her use of magic to Ambrosio Matilda states that when “ I dared to perform those mystic rites, which summoned to my aid a fallen Angel…I saw the Dæmon obedient to my orders; I saw him trembling at my frown, and found, that instead of selling my soul to a Master, my courage had purchased for myself a Slave.”[14] This clearly is a representation of the powerful and controlling magic of the necromancer, exerting one’s will upon the demon, not submitting to servitude but subjecting servitude upon it. Furthermore, when Lewis allows us to witness Matilda performing these rites firsthand with Ambrosio, we are told

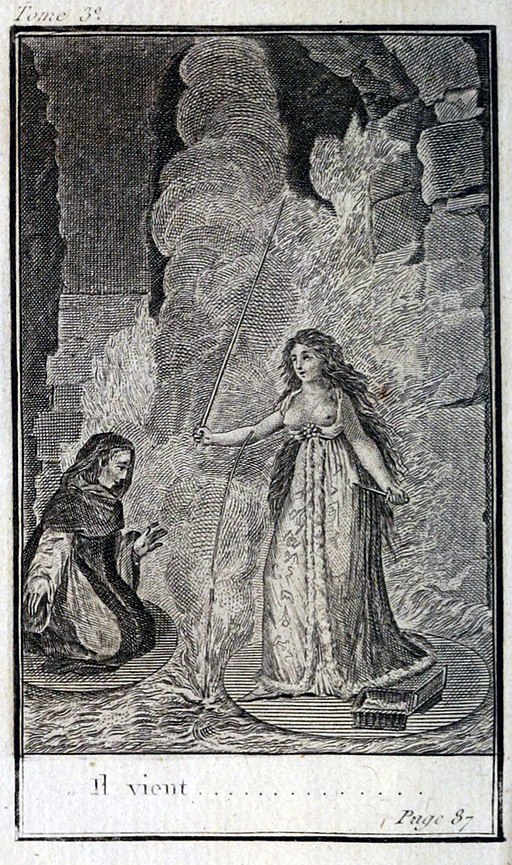

She had quitted her religious habit: She was now clothed in a long sable Robe…. In her hand She bore a golden wand…and began her mysterious rites…. She drew a circle around him, another around herself, and then taking a small Phial from the basket, poured a few drops on the ground before her…. [She] continued her incantations: At intervals She took various articles from the Basket…three Human fingers, and an Agnus Dei[15].[16]

While there is a lot to unpack here, one thing that particularly stands out is the striking visual that Lewis paints. If we refer to the image below, taken from the University of Paris document, we see an almost identical representation of the events depicted in this sixteenth-century illustration of ritual demonic magic. While in the case of Matilda we have a female preforming the ritual, it should be clear from the similarities in the clothes, wand, protective circles on the floor, and submissive behaviour of the invoked demon that magic Matilda is practicing is necromancy, not witchcraft. The fact that Matilda throughout the text has filled the role of an educated male cleric also supports the conclusion that Lewis was drawing from early medieval ideas about magic and sorcery when constructing her character. Most necromancers and practitioners of diabolic magic of this sort were educated elite males, and despite her sex, that is the role Matilda is filling.[17] Now, we must consider why Lewis would choose to have the beautiful Matilda play such a role? A choice that becomes obvious when viewing her as a personification of the collapse of the social order and a manifestation of the anxieties created by the revolution in France.

16th C. Depiction of a Necromancer Summoning a Demon. (Source: The University of Paris, “The University of Paris,” 53.)

Matilda’s representation as a female playing a highly masculine role casts her as a subverting figure and also aligns her with the most traditional figure of femininity in the Judaeo-Christian tradition. By having her subvert the social order and gendered norms in this way, all the while seducing and corrupting Ambrosio, Lewis is actually having Matilda recreate the actions of Eve. Matilda is acting as an agent working to bring about the fall of Ambrosio, just as Eve brought the fall of Adam. Eve, of course, through her actions has come to be seen as bringing not only Adam’s fall but the fall of all mankind. At a time when it appeared that Western European civilization was collapsing in on itself, it is unsurprising to find these allusions to the fall of man in the literature of the period. It is even less surprising that these allusions should be represented through the figure of the witch.

The witch is a figure that plays well into the theme of the social order subverted. Historically, women have been targeted and characterized as witches for this very reason by writers such as Kramer in his Malleus Maleficarum. Women, among other things, are said to be more susceptible to witchcraft because they are “feebler both in mind and body” than men.[19] Women as witches then are an affront to the natural order because, at its most basic level, witchcraft allows women to obtain a power greater than men that they should not naturally possess. Witchcraft provides women “an easy and secrete manner of vindicating themselves” that demonologists historically argued they would otherwise lack due to their innate inferiority.[20] Matilda represents the realization of this fear perfectly. Lewis goes so far as to portray her initially as literally a male, and only later is she revealed to be female. This can be understood as the subversion of the natural order taken to the extreme, women becoming a man. Even after she is revealed to be female, Matilda still plays the dominant role in her relationship with Ambrosio. It is she who seduces him, she who dominates him, ridicules him for his fear, chides him for his hesitancy, she is the one controlling the events, a female dominant over males.[21]

Lewis does portray Matilda’s physical appearance as highly feminine after she is revealed to be a female, but in a way that also plays into historic fears of female empowerment. Just as Eve has been portrayed as a temptress for her role in corrupting Adam, so too have fears of witches acting as temptresses for the devil manifest in the writing of demonological treatises. In Demonolatry, Nicolas Remy writes that one of the ways in which men are first led astray by the devil is with his tempting them through their lust.[22] This then helps to explain why Matilda, despite playing such a Masculine role and despite witches being traditionally stereotyped as old or repulsive, is portrayed as a young and highly alluring beauty.[23] Her beauty is a tool just as much as her magic, she weaponizes that beauty to seduce Ambrosio and guide him in his fall from grace. The depiction of the witch as young and seductive does not align with what might be expected of a stereotypical representation. Lewis, however, is drawing upon the anxieties expressed by demonologists of witches’ sexuality being weaponized to corrupt the pure.[24] The seemly unusual representation is actually deeply rooted in historical fears surrounding the Devil and women. Matilda’s sexual and feminine appearance transforms her into a temptress, a counterpart to Eve.

To conclude, The Monk as the first horror novel written in the English language provides a fascinating opportunity to analyze just how and why representations of witches and witchcraft take the forms they do. In an environment of heightened concern about the collapse of the established social order generated by the anxieties over the revolution in France, it is unsurprising that Lewis would select the female witch as his subject of choice in his debut horror. The witch is a figure that for centuries had been connected with concerns about the subversion of gender roles and the embodiment of anxieties about female empowerment. The characterization of Matilda with the historic figure of the male necromancer and her exertion of dominance over Ambrosio is fascinating. It can be seen as a reflection of both contemporary fears from Lewis’s period, and the long-standing historic anxieties that witches would subvert the natural order and dethrone men from their God-given seat of power. While this analysis is by no means exhaustive, and similar studies could be done into the many other modern representations of witches, it does nicely illustrate a point. Modern representations are shaped as much by the events occurring when they are written as by the historic traditions they draw inspiration from.

[1] Matthew Lewis, The Monk (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016), ix; E.P Thomas, The Making of the English Working Class (London: Penguin Books, 2013), 19-20.

[2] Lewis, The Monk, vii-viii.

[3] Lewis, The Monk, viii.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid., 7.

[6] Ibid., xii-xiv; Thompson, The Making, 85.

[7] Michael David Bailey, “The Feminization of Magic and the Emerging Idea of the

Female Witch in the Late Middle Ages,” Essays in Medieval Studies 19, (2002): 121

[8] The University of Paris, “The University of Paris: A Condemnation of Magic, 1398,” in The Witchcraft Sourcebook, ed. Brian P. Levack (New York: Routledge, 2015), 50.

[9] Ibid., 49-51; Bailey, “The Feminization,” 125-6; Tamar Herzig, “The Demons and the Friars: Illicit Magic and Mendicant Rivalry in Renaissance Bologna,” Renaissance Quarterly 64, no. 4 (Winter 2011): 1028.

[10] Bailey, “The Feminization,” 121.

[11] Ibid., 128.

[12] Heinrich Kramer, “Heinrich Kramer: Malleus Maleficarum, 1486,” in The Witchcraft Sourcebook, ed. Brian P. Levack (New York: Routledge, 2015), 63; Ibid., 68; Nicolas Remy, “Nicolas Remy: The Devil’s Mark and Flight to the Sabbath, 1595,” in The Witchcraft Sourcebook, ed. Brian P. Levack (New York: Routledge, 2015), 91; Pierre de Lancre, “Pierre de Lancre: Dancing and Sex at the Sabbath, 1612,” in The Witchcraft Sourcebook, ed. Brian P. Levack (New York: Routledge, 2015), 121-2.

[13] Bailey, “The Feminization,” 128.

[14] Lewis, The Monk, 206.

[15] The historical significance of the ritual burning of an Agnus Dei cannot be understated. The Agnus Dei is a Catholic religious protective amulet, made of wax from paschal candles blessed by the Pope (Thomas 1971, 31). Not only does Lewis’s inclusion of this hint back to the anticatholic bias prevalent in England at the time, which has already been mentioned, but it also ties the ritual back to a longstanding historical tradition of inversion surrounding beliefs of witchcraft. Agnus Dei’s were intended to serve as defence against demons and the Devil, so using one to summon him is a clear example of a demonic reversal of the Catholic faith (Thomas 1971, 31).

[16] Lewis, The Monk, 211-2.

[17] Herzig, “The Demons,” 1028; Bailey, “The Feminization,” 125.

[18] The University of Paris, “The University of Paris,” 53.

[19] Kramer, “Heinrich Kramer,” 64.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Lewis, The Monk, 52; Ibid., 70-1; Ibid., 180; Ibid., 206.

[22] Remy, “Nicolas Remy,” 89.

[23] Lewis, The Monk, 61-63; Ibid., 71.

[24] Remy, “Nicolas Remy,” 21; Kramer, “Heinrich Kramer,” 65-66.

Writing Details

- Sean D. Dempsey

- June 5, 2020

- 3645

- (emailed to author) Request Now

This work by Sean D. Dempsey is licensed under a Creative Commons CC-BY Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work by Sean D. Dempsey is licensed under a Creative Commons CC-BY Attribution 4.0 International License.- Matilda Summoning Lucifer. Illustration retrieved from https://otn.pressbooks.pub/guidetogothic/chapter/matthew-lewis-excerpt-from-the-monk-1796/

- Tweet