When asked what a witch looks like to a twenty-first century person, it is likely that the said person will describe a woman who is old and ugly, much like the witch in the story Hansel and Gretel or the witch in Snow White. In their trials, early Modern people used the stereotype of the hag witch that we see so much today. The witch of Early Modern Europe is viewed as hag-like with ugly spots on her body, a large nose, and they are often described as mentally unstable or whispering to themselves/demons. The witch in Early Modern Europe is a person to be greatly feared. She could ruin lives by whispering spells or using salves to poison children and cattle; this fear led to mass executions, especially in Germany from the fifteenth century to the seventeenth. It is clear that women, especially those who were older or widowed, were targeted more frequently than men during the witch craze, but it is likely much more complex than a simple difference in gender and subordination of women. Using the primary sources of the trial of Tempel Anneke and Walpurga Hausmännin, this essay will argue that elderly and widowed women were part of a larger sum of prosecutions during the witch trials due to stereotypes surrounding natural changes that come with age, the emphasis on their fertility, and the discriminiation of older women due to poverty.

CHANGES WITH AGE

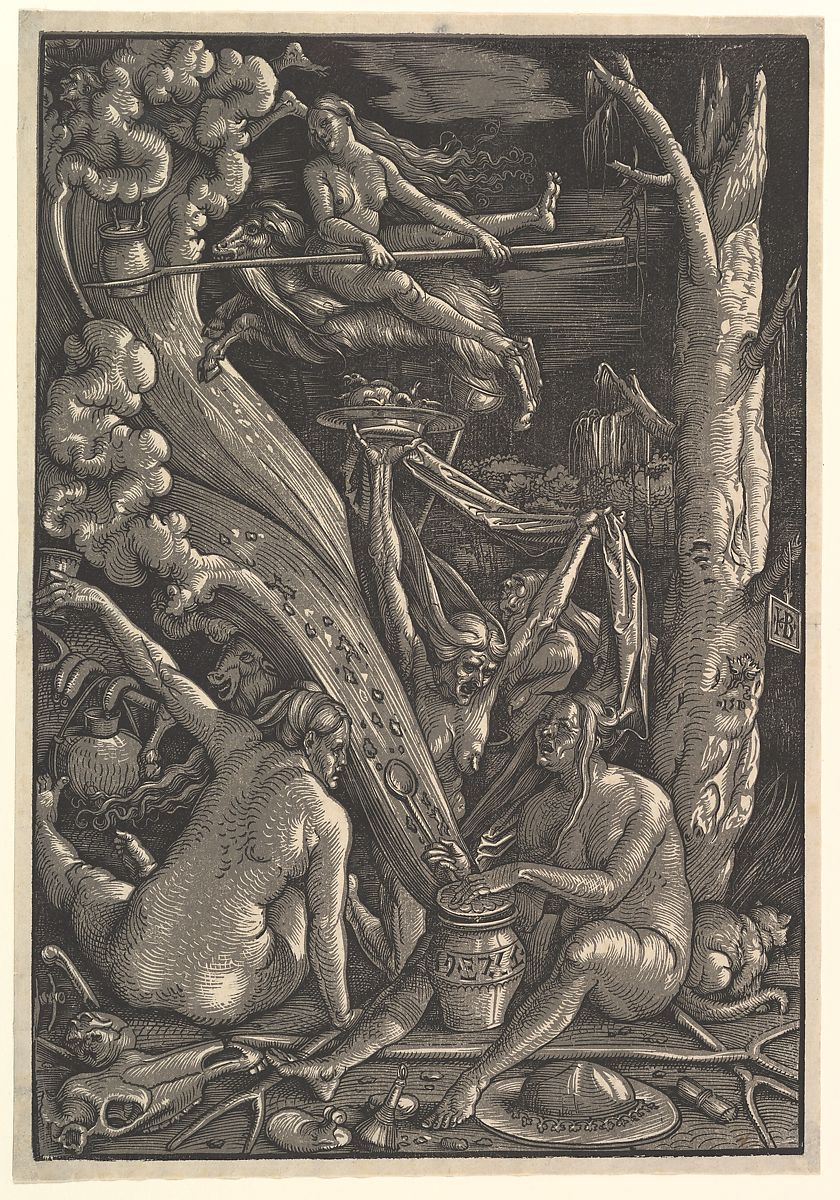

Elderly women and widows were specifically targeted during the Early Modern Witch trials because of the physical and mental changes that came with age which was depicted through popular culture and could be seen in paintings, literature, and general conversations throughout the village. In Wurzburg, out of the 190 women tried for witchcraft, 140 were over 40 years old.1 Research in Early Modern Germany’s statistics surrounding witch trials and age is fragmented, but the Saar and Lippe region shows a significant age group being tried in their 50-60s.2 Therefore, it can be deduced that the older age groups were the most affected by the witch trials of Early Modern Germany. Hans Baldung Grien, a german artist, depicts witches with unruly hair, sagging breasts, a large nose, and a generally ugly appearance.3 During interrogations, women were stripped, shaved completely, and checked for a witches’ mark.4 On Elderly women, this mark could easily be an age spot, or scars that accumulate over time. With the rendition of a stereotypical witch being a generalized elderly woman, hatred and attacks on the elderly due to accusations of witchcraft would become the norm. The hatred towards the elderly was made apparent through Ursula Grön, she was accused of witchcraft and the people of the village were generally disgusted by her presence and wanted her to be burned alive.5 The physical stereotypes of witches following the natural change of an older woman’s body sparked the generalized fear and hatred of elderly women leading to violence and witch accusations against them.

Elderly women were not only targeted for accusations of witchcraft based on the physical changes in their bodies, but it was likely that they were also targeted due to their own mental deterioration. In 1563, Johann Weyer argued in his writings that older women of the time tended to be inconstant in faith and not settled in their minds, making them subject to the Devil’s deceits and more likely to practice witchcraft.6 Old women would tend to mumble to themselves or act out aggressively more than younger generations, this ‘unsettled mind’ would likely be senile psychosis which came with age.7 Some women truly believed they were witches or were convinced by the inquisition, which would be common in elderly women suffering mental deterioration and being given leading questions during interrogation. Women of older ages were alone often as many were widows and William Monter speculates that solitary women relied on magic to enact revenge or add excitement to their lives.8 Elderly people also suffered memory loss from Alzheimers or just as a general sign of aging and during interrogation these women were asked to recite prayer.9 Naturally, this could be very difficult and if they could not recite it they would be submit to further interrogation as a witch. The natural mental changes that come with aging could give the inquisition more reason to subject elderly women to the torture and interrogations of the witchcraft trials.

The length of the woman’s reputation is an important aspect to note regarding why elderly women were targetted more often in Early Modern European witch trials. Most people who were accused of witchcraft could have up to forty years of informal accusations towards them before a formal trial began.10 In the trial of Walpurga Hausmännin, her accusations dated back thirty-one years and she confessed to crimes one to twelve years ago.11 Tempel Anneke was sixty-three at the time of her formal trial, but she admitted to having intercourse with the Devil much earlier in her lifetime.12 It can then be argued that elderly women were only targeted as witches because of the multiple accusations that the procured over time, not their specific age. In addition to this, most of the women would be formally accused once their husbands had died and they became widows. This was because the husbands could protect the woman from any formal accusations made against her, but once he was dead there would be no formal male to defend her reputation13 The lengthy amount of time between informal and formal accusations, as well as the lack of a defense from a male figure would cause an elderly woman to confess to crimes she did not commit and for the interrogators to see her as guilty until proven innocent.

FERTILITY

During the witch trials in Early Modern Europe the fertility or ability to be a proper mother was heavily emphasized. Because of this focus, women experiencing menopause were targeted in the witch trials. During this time, a woman’s worth was often based off of their fertility and menstrual cycle, it was believed that if there was no menstrual cycle occurring, there were too many impurities in the body14 A woman could also be targeted in witch trials if she was sexually promiscuous but unable to bear children as this was very disturbing to Early Modern European society.15 There was a sexual undertone in the way tortures and interrogations were set. Women were shaved and bodies investigated, and sometimes left naked because there was a fear that there was magic in their clothing.16 This would lead to women confessing quicker in order to avoid further shame. The interrogators may have assumed that witches did not care who saw them naked as they were considered to be shamelessly sexually promiscuous even if they were going through menopause. In Tempel Anneke’s trial, her confession of having intercourse with the Devil could represent the societal disgust that came with the idea of post-menopausal women having sex.17 Women who are experiencing menopause also suffer from irritability and socially disruptive behaviours.18 These socially disruptive behaviours could show itself as an aggressive act, even if there is no aggression there. Because magic was seen as a weapon, this aggression could cause fear in communities and ignite the idea that any person who uses magic to harm others should be snuffed out.19

The emphasis on infanticide in witch trials of Early Modern Europe could also be a reason that infertility gives a community reason to submit a formal accusation against an older woman. New mothers who have anxieties for their babies or have had their children suddenly die may blame the older women of the village who are no longer is able to produce children.20 In Walpurga’s trial, she admits to an extreme amount of infanticide cases as she was a formally licensed midwife in Dillingen, 1587.21 Walpurga admits to creating salves to kill children and physically killing them in order to eat them.22 The confessions of witches killing children could correlate with their own infertility, with villages seeing an older woman’s attack on a newborn as revenge for their inability to have a child. In the case of Appolonia, she was thought of as lacking maternal nature and therefore was targeted for that. Appolonia was accused of tying her belt too tight over her pregnant belly, which ended up killing her baby.23 Her inability to be a proper mother caused her to be in the focus of witch accusations. The heavy focus of infanticide in witchcraft accusations and trials reference the lack of youth in the women accused of witchcraft, such as Appolonia and Walpurga. Post-menopausal women were specifically targetted in the witch trials of Early Modern Europe because of the direct correlation between the impurity of infertility and the search for youth and revenge through infanticide. Because of this, elderly women suffered more accusations and executions during witch trials.

ECONOMICS

In poverty stricken villages, tensions between people of the community were very likely. This kind of disruption in the communities could lead to accusations of witchcraft amongst the villagers. The most likely of people to rely on others for financial aid would be elderly and widowed women as there was a pattern of conflict through economic and population issues.24 The women accused of witchcraft were likely to be poor, marginalized outsiders, but integral members of the community.25 The elderly women affected by poverty would often be angry towards socio-cultural restrictions, and they would act out in anger.26 This would cause conflict in the community, and then lead to accusations against the older woman. Single or widowed women would also be targeted because they were more dependant on the assistance of their neighbours which made them more likely to be involved in problematic exchanges about material goods.27 In addition to this, the worsening of old age would increase the likability for an elderly woman to act out aggressively, leading to the belief that she was a witch. Economically, widows were of lower status, and because of this they were accused much more than people of higher economic standing. This segregation between the middle/upper class and the poorer classes caused tension and accusations of witchcraft, especially when the person of higher economic standing began to have their cattle die or their farms rot. It was easier for them to blame the witch than believe that God was not on their side regarding wealth.

In Tempel Anneke’s case, the city of Harxbuttal was poverty stricken for thirty years before her trial, and while Anneke was also a well known member of her town but she was dependant on her family financially.28 When the community’s economic gain was at risk due to people and their calves dying, Anneke became an easy target as she would have reason to seek revenge. Ursula Grön was poor and begged for items and food from her neighbors, when she was denied more food she became a feared woman because of a rise in tensions and previous witchcraft accusations.29 This went on until a formal accusation was made against her. The case of Walpurga is interesting because her position as a midwife made her a well known member of society. However, during her trial, Walpurga admits to having sex with the Devil for a lead coin and selling her soul to the Devil to aid her in poverty.30 Walpurga conforms to previous stereotypes of witches being impoverished, which shows that this stereotype was a reason why elderly and widowed women were targetted during the witch trials of Early Modern Europe.

Elderly women were targetted more often than any other person during the Early Modern European witch trials, displaying a hatred and disdain towards elders. This was because of their physical and mental changes that came with aging plus the length of their reputation; a woman would be targeted if she showed any of the natural signs of aging. An elderly woman’s infertility could be seen as dirty because she would still be sexually active but not in the hopes to have a child, or she could act out in aggression towards youth through infanticide. Lastly, because elderly women suffered economic strife more often than a younger person there would be more conflict between neighbors, which could lead to more accusations against older women. The Early Modern witch trials show that gender and age based violence was a very prevalent force even in the sixteenth and late seventeenth century. It shows that women, especially those who were elderly, were targeted based on the issues that come with gender and age.

Endnotes

- Lyndal Roper, “Crones,” in Witch Craze (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004), 160.

- Lyndal Roper, “Crones,” in Witch Craze (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004), 161.

- Lyndal Roper, “Crones,” in Witch Craze (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004), 164.

- Lyndal Roper, “Interrogation and Torture,” in Witch Craze, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004), 49.

- Lyndal Roper, “Crones,” in Witch Craze (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004), 170.

- Alison Rowlands, “Witchcraft and Old Woman in Early Modern Germany,” Past & Present 1, no. 173 (2001): 52.

- Alison Rowlands, “Witchcraft and Old Woman in Early Modern Germany,” Past & Present 1, no. 173 (2001): 52.

- Edward Bever, “Witchcraft, Female Aggression, and Power in the Early Modern Community,” Journal of Social History 35, no. 2 (2001): 959.

- Lyndal Roper, “Interrogation and Torture,” in Witch Craze, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004), 55.

- Alison Rowlands, “Witchcraft and Old Woman in Early Modern Germany,” Past & Present 1, no. 173 (2001): 78.

- “The Confession of Walpurga Hausmännin, 1587,” in Witchcraft Sourcebook, ed. by Brian Levack (New York: Routledge, 2015), 194-196.

- “Folio 45,” in The Trial of Tempel Anneke: Records of a Witchcraft Trial in Brunswick, Germany, 1663, Second Edition, ed. by Dähms, Barbara and Peter A. Morton (Toronto, Ontario: University of Toronto Press, 2017), 119.

- Alison Rowlands, “Witchcraft and Old Woman in Early Modern Germany,” Past & Present 1, no. 173 (2001): 65.

- Lyndal Roper, “Crones,” in Witch Craze (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004), 162-164.

- Lyndal Roper, “Crones,” in Witch Craze (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004), 165.

- Lyndal Roper, “Interrogation and Torture,” in Witch Craze, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004), 54.

- “Folio 45,” in The Trial of Tempel Anneke: Records of a Witchcraft Trial in Brunswick, Germany, 1663, Second Edition, ed. by Dähms, Barbara and Peter A. Morton (Toronto, Ontario: University of Toronto Press, 2017), 119.

- Edward Bever, “Witchcraft, Female Aggression, and Power in the Early Modern Community,” Journal of Social History 35, no. 2 (2001): 967.

- Edward Bever, “Witchcraft, Female Aggression, and Power in the Early Modern Community,” Journal of Social History 35, no. 2 (2001): 959.

- Alison Rowlands, “Witchcraft and Old Woman in Early Modern Germany,” Past & Present 1, no. 173 (2001): 58.

- “The Confession of Walpurga Hausmännin, 1587,” in Witchcraft Sourcebook, ed. by Brian Levack (New York: Routledge, 2015), 193.

- “The Confession of Walpurga Hausmännin, 1587,” in Witchcraft Sourcebook, ed. by Brian Levack (New York: Routledge, 2015), 195.

- Alison Rowlands, “Witchcraft and Old Woman in Early Modern Germany,” Past & Present 1, no. 173 (2001): 61.

- Edward Bever, “Witchcraft, Female Aggression, and Power in the Early Modern Community,” Journal of Social History 35, no. 2 (2001): 958.

- Edward Bever, “Witchcraft, Female Aggression, and Power in the Early Modern Community,” Journal of Social History 35, no. 2 (2001): 958.

- Edward Bever, “Witchcraft, Female Aggression, and Power in the Early Modern Community,” Journal of Social History 35, no. 2 (2001): 967.

- Alison Rowlands, “Witchcraft and Old Woman in Early Modern Germany,” Past & Present 1, no. 173 (2001): 62.

- “Historical Background,” in The Trial of Tempel Anneke: Records of a Witchcraft Trial in Brunswick, Germany, 1663, Second Edition, ed. Dähms, Barbara and Peter A. Morton (Toronto, Ontario: University of Toronto Press, 2017), xix.

- Lyndal Roper, “Crones,” in Witch Craze (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004), 171.

30. “The Confession of Walpurga Hausmännin, 1587,” in Witchcraft Sourcebook, ed. by Brian Levack (New York: Routledge, 2015), 194.

Writing Details

- Sarah Milligan

- June 8, 2020

- 3413

This work by Sarah Milligan is licensed under a Creative Commons CC-BY Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work by Sarah Milligan is licensed under a Creative Commons CC-BY Attribution 4.0 International License.- "The Witches" by Hans Baldung (called Hans Baldung Grien) 1510. Found on https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/336235

- Tweet