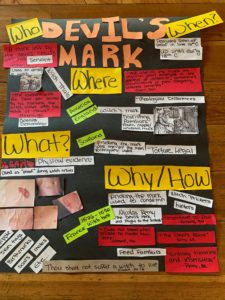

For my final project, I chose to do a who/what/where/when/why collage on the Devil’s mark and how it was used during the witch trials. I chose this style for my artistic representation because it offers important information in a clear, visual manner. I color coded the poster with quotations in red so they are easy to identify. By using a combination of quotations from my research, images, and my own words, I explain the Devil’s Mark and its impact on the witch trials with a focus on Early Modern Europe.

For my final project, I chose to do a who/what/where/when/why collage on the Devil’s mark and how it was used during the witch trials. I chose this style for my artistic representation because it offers important information in a clear, visual manner. I color coded the poster with quotations in red so they are easy to identify. By using a combination of quotations from my research, images, and my own words, I explain the Devil’s Mark and its impact on the witch trials with a focus on Early Modern Europe.

The Devil’s Mark, although varying in its concept throughout Europe, became a prominent form of proof of witchcraft during the witch trials. I initially chose this topic because I was intrigued by Nicholas Remy’s document, “The Devil’s Mark and Flight to the Sabbath.” His depiction of the use of unusual marks as physical proof to identify a witch interested me. I also resonate with the concept of the Devil’s Mark because I have a prominent birthmark that, had I been born during Early Modern Europe, I could have been labelled a witch. Since reading Remy’s primary source, I have researched the Devil’s Mark and how it was perceived in different parts of Europe, specifically England and Scotland.

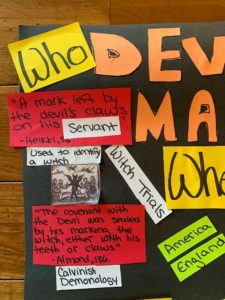

My poster analyzes five questions: who, what, where, when, and why/how in relation to the Devil’s Mark. The question of “who” relates to who the Devil’s Mark affected. The mark was used during the witch trials to identify a witch. Almond discusses in his book, The Devil: A New Biography, that the Protestant belief system, and more specifically the Calvinist demonology, introduced the idea of the pact with the devil, sealed with a mark upon his servant.[i] In many areas throughout Europe it became known as a “covenant with the Devil… sealed by his marking the witch, either with his teeth or claws.”[ii] The image in this section is meant to represent the Devil with his followers of witches. This depiction has the Devil with sharp claws, surrounded by his servants, with familiars flying overhead.[iii]

The question of “what” asks what the Devil’s Mark was. Remy referred to the mark as being “the Devil’s brand.”[iv] It was used as physical evidence during the witch trials. Unusual markings such as skin tags, moles, birthmarks, nipples, and scars could be considered “a mark left by the Devil’s claws on his servant’s body.”[v] The images used in this section are meant to represent examples of things that could have been considered a Devil’s Mark.[vi]

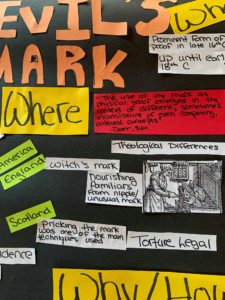

The Devil’s Mark had theological differences throughout Europe and America. The “where” portion of this poster is meant to address some differences, mainly between England and Scotland. The use of the mark as physical proof “emerged in the context of different, sometimes inconsistent, or even competing, cultural concepts.”[vii] In England and America, “the mark was initially regarded as an extra nipple where the witch’s familiar suckled.”[viii] This concept was eventually modified as continental ideas of the Devil’s Mark were introduced to England. The image here represents a witch and her familiars.[ix] Where England focused on the mark to nourish a witch’s familiar, Scotland had a different view: “in Scotland, the mark signified a covenant between the witch and the Devil.”[x] This led to ‘pricking’ being one of the main techniques used to identify a witch in Scotland. Scotland’s acceptance of torture as a means of identifying a witch meant a person could have their mark pricked until they confessed.[xi] Although both countries used the mark as physical proof, there were theological differences between England and Scotland regarding the Devil’s Mark.

The “when” section of the poster addresses the time frame of the use of the Devil’s Mark. According to Almond, the Devil’s mark became a prominent form of proof in many European countries in the late sixteenth century, up until the early eighteenth century.[xii] Remy’s witch hunt campaign in France was largely dependant on using the Devil’s Mark to identify a witch. These campaigns began in 1576 and ended in 1592.

The final section of the poster is the “why/how.” The Devil’s Mark is significant because it was used as a form of physical evidence of witchcraft throughout Europe and America. Although described as unusual, birthmarks, skin tags, scars, moles, etc. are common amongst people and therefore were an easy way to implicate a person in witchcraft. Both theologies, whether the mark was used to feed familiars or as a pact with the Devil, believed the mark to be “entirely bloodless and insensitive to pain.”[xiii] It was believed that “areas exposed to extreme cold would lose their sensitivity and, when touched by the talons of the Devil’s icy cold body, they remained permanently affected.”[xiv] Using the mark for physical evidence led to official witch prickers and witch hunters seeking out unusual marks and performing bodily searches on suspected witches.[xv] The Devil’s Mark became a prominent form of evidence used to persecute those people accused of witchcraft.

The sources I have used for my research provided information regarding who the Devil’s Mark impacted, what it was, where and when it was prominent, and why it was important. The sources offer a significant amount of information, thus I decided to make a poster collage to display my research. The Devil’s mark was used as physical proof during the witch trials, making it an important topic of study.

Bibliography

“AboutKidsHealth.” https://www.aboutkidshealth.ca/article?contentid=455&language=english.

Almond, Philip. “The Devil and the Witch.” In The Devil: A New Biography, 118-140.

Cornell University Press, 2014.

Bev, G. “What Is a Witch’s Mark?” Exemplore, June 6, 2019. https://exemplore.com/wicca-

witchcraft/What-is-a-Witchs-Mark.

“Birthmark Removal.” Krasa Skin and Hair Clinic.

http://www.krasaclinic.com/treatment/treatments/

Darr, Orna Alyagon. “The Devil’s Mark: a Socio-Cultural Analysis of Physical Evidence.”

Continuity and Change 24, no. 2 (October 2009): 361–87.

https://doi.org/10.1017/s0268416009007218.

“Familiar.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, last modified May 26, 2020.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Familiar.

Guilford, Gwynn. “Why Did Germany Burn so Many Witches? The Brutal Force of Economic

Competition.” Quartz. Quartz, July 24, 2018. https://qz.com/1183992/why-europe-was-overrun-by-witch-hunts-in-early-modern-history/.

McDonald, S. W. “The Devil’s Mark and the witch-prickers of Scotland.” Journal of the Royal

Society of Medicine, vol. 90 (September 1997): 507-511.

Pihlajamäki, Heikki. “Swimming the Witch, Pricking for the Devils Mark: Ordeals in the

Early Modern Witchcraft Trials.” The Journal of Legal History 21, no. 2 (2000): 35–58.

https://doi.org/10.1080/01440362108539608.

Remy, Nicolas. “The Devil’s Mark and Flight to the Sabbath.” In The Witchcraft

Sourcebook, edited by Brian Levack, 82-87. Taylor and Francis Group, 2003

WillowWinsham. “The Devil’s Own: Devil Marks.” The Devil’s Own: Devil Marks, January 1,

- http://winsham.blogspot.com/2014/07/the-devils-own-devil-marks.html.

[i] Philip C. Almond, “The Devil and the Witch,” in The Devil: A New Biography, (Cornell University Press), 135.

[ii] Almond, “The Devil and The Witch,” 136.

[iii] Guilford, Gwynn. “Why Did Germany Burn so Many Witches? The Brutal Force of Economic Competition.” Quartz. Quartz, July 24, 2018. https://qz.com/1183992/why-europe-was-overrun-by-witch-hunts-in-early-modern-history/.

[iv] Nicolas Remy, “The Devil’s Mark and Flight to the Sabbath,” in The Witchcraft Sourcebook, ed. Brian Levack (Taylor and Fracis Group), 83.

[v] Heikki Pihlajamäki, “Swimming the Witch, Pricking for the Devils Mark: Ordeals in the Early Modern Witchcraft Trials,” The Journal of Legal History 21, no. 2 (2000): 36.

[vi] WillowWinsham. “The Devil’s Own: Devil Marks.” The Devil’s Own: Devil Marks, January 1, 1970. http://winsham.blogspot.com/2014/07/the-devils-own-devil-marks.html.

“Birthmark Removal.” Krasa Skin and Hair Clinic. http://www.krasaclinic.com/treatment/treatments/

“AboutKidsHealth.” https://www.aboutkidshealth.ca/article?contentid=455&language=english.

[vii] Orna Alyagon Darr, “The Devil’s Mark: a Socio-Cultural Analysis of Physical Evidence.” Continuity and Change 24, no. 2 (October 2009): 361.

[viii] Darr, “The Devil’s Mark,” 368.

[ix] “Familiar.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, May 26, 2020. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Familiar.

[x] S. W McDonald, “The Devil’s Mark and the witch-prickers of Scotland.” Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, vol. 90 (September 1997): 507.

[xi] Darr, “The Devil’s Mark,” 368.

[xii] Almond, “The Devil and the Witch,” 136.

[xiii] Remy, “The Devil’s Mark and Flight to the Sabbath,” 83.

[xiv] Almond, “The Devil and the Witch,” 136.

[xv] Almond, “The Devil and the Witch,” 138.

Writing Details

- Nevada Hinton

- June 8, 2020

- 1801

- (emailed to author) Request Now

This work by Nevada Hinton is licensed under a Creative Commons CC-BY Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work by Nevada Hinton is licensed under a Creative Commons CC-BY Attribution 4.0 International License.- Nevada Hinton

- Tweet