The period between 1550 and 1700 shows the height of the Scottish witch-hunts where over a thousand people were executed for witchcraft.[1] These trials show significant evidence related to sexuality, specifically demonic sex; however, connecting witchcraft and sexuality is complex. The emphasis on sexuality, in connection to witchcraft, stems from the idea that women are more inherently sexual than men, which is important because approximately eighty-five percent of witches in Scotland were women.[2] This idea enforced by elite men who controlled the court system in Scotland. A large part of connecting sexuality, explicitly demonic sex, to witches was implemented during the questioning process of the witch trials. The emphasis on sexuality in witchcraft was highly influenced by the Protestant reformation and other legal changes happening at the time of the Scottish witch hunts. Understanding the context and legality of witchcraft sheds light on its connection to sexuality. To further understand the connection between witchcraft and sexuality in early modern Scotland, we need to look at women’s sexuality and how this connected to witches, demonic sex, and the elite implication of sexuality in witch trials.

During the early modern period, Scotland began attempting to regulate morality. Witchcraft beliefs had strong ties to religious beliefs, which were incredibly influential during the reformation in Scotland.[3] Due to the Protestant reformation, Scotland began implementing an active godly state which brought on the Parliament of 1563.[4] The parliament of 1563 made many moral acts crimes, this included fornication, incest, infanticide, sodomy, prostitution, witchcraft, and scolding, which was an offence where all of the offenders were women.[5] With this we see Scotland attempting to regulate morality within the country and that these acts are all related to sex. These crimes were very significant for Scottish authorities, especially witchcraft. King James VI stated that “surely then, I think, since this crime ought to be severely punished,” and “Judges ought indeed beware whom they condemn, for it is great a crime.”[6] Before this construction of an active, integrated, and godly state women were incredibly less likely to be in court for any reason as the only authority was of their fathers or husbands.[7] When we set witchcraft within a broader criminal context we can widen our understanding of it and the possibilities within it.[8]

Due to these circumstances around the illegality of sexual acts historians saw an increase in the witch-hunts. To understand the connection between witchcraft and sexuality, we need to look at how women were perceived during the early modern period. Women made up approximately 84 percent of all witches, specifically between 1661 and 1662, this is due to the assumption that women were weaker and more carnal.[9] This belief implied that women would be more prone to reject faith and have sex with the devil.[10] The presumed excessive sexuality of women was therefore considered a primary cause of their sensitivity to witchcraft and the devil.[11] This is the principal reason why most witches were women and why it includes significant connections to the sexual nature of being a witch. The typical witch could be described as female, poor, older, and settled within the community.[12] Although, it is important to remember that during times of panic the people who were accused widened outside of this picture. Understanding the perceptions of women is important, as is recognizing individual reputations. During the early modern period, one’s reputation was incredibly valuable during any criminal trial. A women’s reputation for honesty, her sexual history, could be her most important alibi during a witch hunt.[13]

While understanding how women’s sexuality is viewed in Scotland during the early modern period we can further understand why sexuality is connected to witchcraft. Women with reputations for being sexually promiscuous or breaking gender norms were at risk of being accused of witchcraft. Elizabeth Maxwell, an accused witch from 1650, had uncontrolled verbal behaviour, Helen Cass was widely known to be sexually promiscuous, and Helen Concker had committed fornication with John Wysurd before being committed to the tollbooth for witchcraft.[14] Those who uttered spells and words like witches were violating gender norms by breaking their silence and capitalizing on the power of words.[15] This had even become a crime on its own with the Parliament of 1563 and scolding.[16] These cases are examples of how a women’s sexuality put her in danger and connected her to witchcraft.

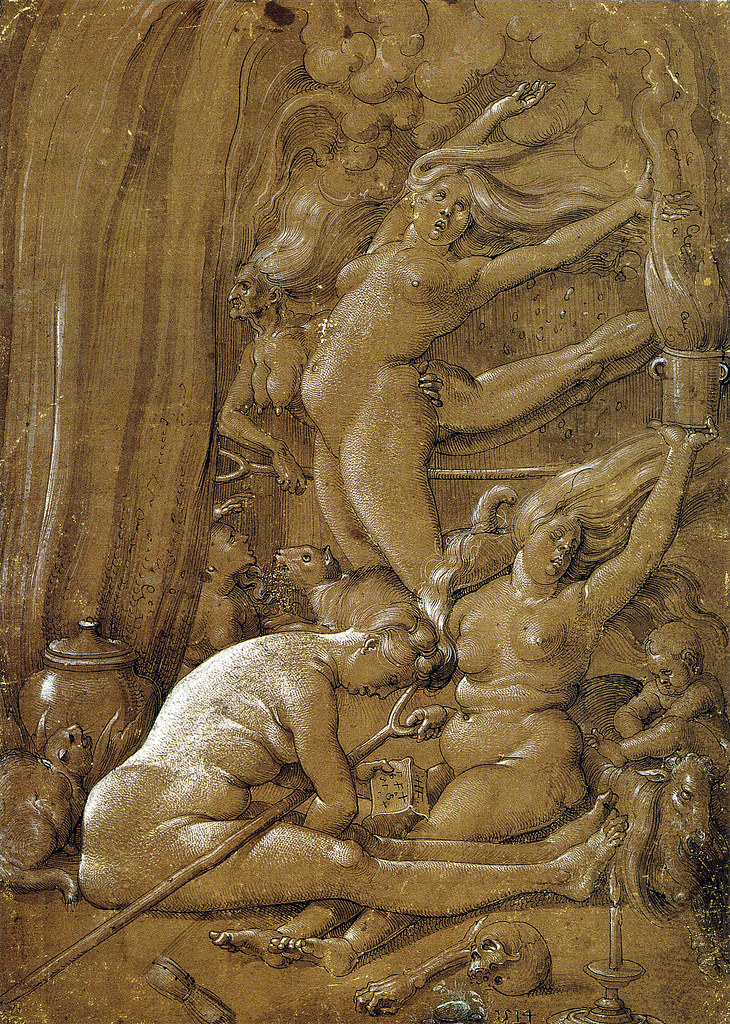

Women’s association with witchcraft was a result of the church and states promotion of moral conformity, which often sought to suppress and demonize sexuality.[17] When examining the witch trials a certain image can be seen, particularly concerns with speech and sexuality, which were often attached to women.[18] These aspects are seen as critical to the witch figure during this period.[19] Due to the connection between deviant sexuality and witches women could be accused of witchcraft despite having no implications of maleficia, bad magic. Several women accused of witchcraft had previously been suspected of or even prosecuted for various forms of moral deviance.[20] Issobell Fergussone had been accused of being a witch in 1661, this is because she had already been accused of fornication and adultery.[21] Cases like Fergussone show historians that women could be easily caught in the witch panic because of their past. The witch trial of Janet McMuldroch and Elspeth Thomsone in 1671 shows the court’s concern with documenting and disciplining the supposed deviant sexuality of accused witches.[22] Women were seen as highly sexual and this is a factor in why sexuality was largely attached to witches. Goodare shows a painting by Hans Baldung Grien which depicts female witches who are naked and provocatively placed.[23] This shows us that women and witches were seen as highly criticized at the same time as being sexual beings, Goodare compares the piece to modern pornography.[24] Hans Baldung Grien’s painting shows popular views of women and witches during the early modern period. This societal view of women during the early modern period in Scotland is a significant reason why witchcraft was highly sexualized.

Demonic sex, sex with the devil, was a central part of witches’ sexuality during the witch trials. Scottish witches were charged with worshipping the devil as well as having sex with him, which became standard features in Scottish accounts of the demonic pact.[25] Scottish authorities believed that when women made a pact with the devil, which was an integral part of being a witch, she would have sex with him.[26] Sex with the devil was a female aspect of witchcraft, as it was not mentioned in the majority of male witch trials.[27] It is important to examine trial records to further understand the relationship between witches and the devil. This is because of the significant evidence we see within the trials, particularly the descriptions found in confessions. The trial of Janet Barker and Margaret Lauder from 1643 is an important example of the demonic aspects of witchcraft during the witch hunts in Scotland.[28] These two women were charged with both worshipping and having sex with the devil.[29] It also states that she “confessed in her examination that she has had divers times carnal copulation with the devil both in her own little shop and in the said late Janet Cranstoun her house and had ado with him [in her] naked bed, who was heavy above her like an ox not like another man.”[30] She also confessed that the devil would come to her and lay with her like a dog.[31] Another case is of Janet McMuldroch and Elspeth Thomsone, where the Justiciary court records show indictments of diabolism with both women accused of entering into a pact with Satan, being his servant, receiving his marks, and having sex with him.[32] Their trial significantly emphasizes their participation in the unnatural sexual relationship with Satan.[33] Other cases that describe sex with the devil are Jonet Braidheid and Issobell Gowdie, both from 1662.[34] Braidheid described the devil as “as cold as spring well water inside of her,” as well as the devil giving her money after sex.[35] Gowdie stated that younger women had greater pleasure in sex with the devil than with their husbands.[36] These are two things that were significantly debated amongst demonologists and the elite. They discussed how the devil had no blood, therefore his penis and semen would be incredibly cold.[37] It was also debated whether or not women would enjoy this sex, as it is described differently throughout the trials. Demonic sex was an integral part of Scottish witch trials during the early modern witch hunts and is particularly significant in the discussion of witchcraft and sexuality.

A vital part of why there is a significant presence of sexuality in relation to witchcraft is because of the elite discourse surrounding it. The historiography surrounding witchcraft and sexuality acknowledges that elite authorities were concerned with female sexual behaviour and were the main reason sexuality was so integral in witchcraft. Dye discusses sexuality and states that “the fact that these sexual stereotypes were almost always associated with the ‘confessions’ of witches, and were hardly present in the depositional evidence against alleged witches, has been taken to indicate the presence of an elite witch belief system that was distinct from peasant belief.”[38] The local accusations of witches did not include making a pact or having sex with the devil.[39] Demonic sex entered into interrogations because the interrogators wanted it there.[40] An example of this is the case of Janet McMuldroch and Elspeth Thomsone from 1671.[41] McMuldroch and Thomsone were accused of witchcraft due to their wilful and disorderly speech, but in the course of their trial, they were also accused of participating in an unnatural sexual relationship with the devil.[42] In many cases like McMuldroch and Thomsone, the pact and sexual relationship with the devil were added into the charges during the later stages of the judicial process.[43] This case and others like it show that sexuality was not the main concern for locals who feared witches. Scottish witchcraft has been characterized by its neighborhood nature and the tendency to level accusations within a closely bounded community.[44] Although, the subjugation of witches was judicially conducted based on elite beliefs surrounding the demonic pact, demonic sex, and the witches’ Sabbath.[45] The elite discourse in Scotland surrounding witchcraft had originated from what was thought to be “popular practice.”[46] This elite witch belief had emphasized a witch’s sexual and diabolical nature.[47] Although, these ideas were often debated during this period and this is why sex took various forms depending on the women’s imagination and pressure from the interrogator.[48] Therefore interrogators would give a little prompting for the witch to get what was seen as the right answer.[49] Judicial torture was discouraged and disallowed by the Privy Council, yet it was still used illegally in the localities.[50] Specifically sleep deprivation, which had an obscure legal status, had appeared more commonly in Scotland during the early modern period.[51] The acts of torture and sleep deprivation would help further the prompting given by interrogators to further their agenda for the trial. The main reason for witchcraft being highly related to sexuality is due to the elite discourse surrounding witchcraft. The elite ideas entered into interrogations and were used to influence witches during their confessions. This is a significant reason as to why witches are seen as highly sexual.

During the height of the Scottish witch-hunts from 1550 until 1700 over a thousand people were executed for witchcraft.[52] The Scottish witch trials show significant evidence relating witchcraft to sexuality, specifically demonic sex; however, making this connection between witchcraft and sexuality is highly complex. Sexuality and witchcraft were heavily influenced by the societal views that women were more inherently sexual than men, therefore more prone to become witches.[53] This idea significantly impacted the witch hunts and this is seen in that eighty-five percent of witches in Scotland were women.[54] These societal ideas were enforced by elite men who also controlled the court system in Scotland. A major part of connecting sexuality, most importantly demonic sex, and witchcraft was implemented during the interrogation process of witch trials. Sexuality and witchcraft were influenced by the protestant reformation and legal changes occurring during Scotland during this time, such as the Parliament of 1563. The context surrounding the legality of witchcraft helps us understand the connection between witchcraft and sexuality. While looking at this connection we need to examine women’s sexuality and the application to witches, demonic sex, and the elite implications of sexuality within the witch trials.

[1] Julian Goodare, “Women and the Witch-Hunt in Scotland,” Social History 23, no. 3 (1998): 289.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Thomas Brochard, “Scottish Witchcraft in a Regional and Northern European Context,” Magic, Ritual, and Witchcraft (2015): 44.

[4] Goodare, “Women and the Witch-Hunt,” 293-294.

[5] Ibid., 294.

[6] King James VI, “Daemonologie,” The Witchcraft Sourcebook, ed. Brian P. Levack (New York: Routledge, 2015), 159.

[7] Goodare, “Women and the Witch-Hunt,” 293.

[8] Brochard, “Scottish Witchcraft,” 63.

[9] Brian P. Levack, “The Great Scottish Witch Hunt of 1661-1662,” Journal of British Studies 20, no. 1 (1980): 100.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Sierra Dye, “To Converse With The Devil? Speech, Sexuality, and Witchcraft In Early Modern Scotland,” International Review of Scottish Studies 37 (2012): 23.

[12] Goodare, “Women and the Witch-Hunt,” 290.

[13] Dye, “To Converse With The Devil?” 14.

[14] Dye, “To Converse With The Devil?” 15, and Levack, “The Great Scottish Witch Hunt,” 101.

[15] Dye, “To Converse With The Devil?” 17.

[16] Goodare, “Women and the Witch-Hunt,” 293.

[17] Dye, “To Converse With The Devil?” 12.

[18] Ibid., 10.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Levack, “The Great Scottish Witch Hunt,” 101.

[21] Julian Goodare, Lauren Martin, Joyce Miller and Louise Yeoman, “The Survey of Scottish Witchcraft,” http://www.shca.ed.ac.uk/witches/ (archived January 2003, accessed June 7th, 2020).

[22] Dye, “To Converse With The Devil?” 10.

[23] Julian Goodare, The European Witch-Hunt (London: Routledge, 2016): 296-297.

[24] Ibid.

[25] “The Trial of Janet Barker and Margaret Lauder at Edinburgh, 1643,” In The Witchcraft Sourcebook, ed. Brian P. Levack (New York: Routledge, 2015), 269 and Dye, “To Converse With The Devil?” 25.

[26] Goodare, “Women and the Witch-Hunt,” 294.

[27] Dye, “To Converse With The Devil?” 24.

[28] “The Trial of Janet Barker and Margaret Lauder,” 269.

[29] Ibid.

[30] Ibid., 270.

[31] Ibid., 271.

[32] Dye, “To Converse With The Devil?” 9-10.

[33] Ibid., 10.

[34] Goodare, Martin, Miller, and Yeoman, “The Survey of Scottish Witchcraft.”

[35] Ibid.

[36] Ibid.

[37] Dye, “To Converse With The Devil?” 24.

[38] Ibid., 27-28.

[39] Levack, “The Great Scottish Witch Hunt,” 100.

[40] Goodare article 295

[41] Dye, “To Converse With The Devil?” 10.

[42] Ibid., 9-10.

[43] Ibid., 21.

[44] Brochard, “Scottish Witchcraft,” 46.

[45] Ibid.

[46] Ibid., 70.

[47] Dye, “To Converse With The Devil?” 23.

[48] Goodare, “Women and the Witch-Hunt,” 294.

[49] Ibid., 295.

[50] Michael Wasser, “The Privy Council and the Witches: The Curtailment of Witchcraft Prosecutions in Scotland, 1597-1628,” The Scottish Historical Review 82, no. 213 (2003): 34.

[51] Wasser, “The Privy Council and the Witches,” 34.

[52] Goodare, “Women and the Witch-Hunt,” 289.

[53] Ibid.

[54] Ibid.

Writing Details

- Rebecca Campbell

- June 14, 2020

- 3082

- (emailed to author) Request Now

This work by Rebecca Campbell is licensed under a Creative Commons CC-BY Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work by Rebecca Campbell is licensed under a Creative Commons CC-BY Attribution 4.0 International License.- Hans Baldung Grien, "Hexen" (1514)

- Tweet